This article is exploring the role of dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts in the relationship between personality traits and psychological distress in Australian University students.

Abstract

The impact of dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thinking upon clients presenting with personality-related psychological distress is an important clinical area of investigation as it informs psychological interventions. Despite this, there is limited research in this area. Thus, this study had two main aims: (1) examine the interrelationships between maladaptive personality traits, dysfunctional attitudes, unhelpful thinking, and psychological distress; and (2) explore the potential mediating roles of dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thinking on the relationship between maladaptive personality traits and psychological distress. A convenience sample of 728 undergraduate psychology students (mean age: 31.57 years; 76% female) completed an online questionnaire for course credit. The results supported the first hypothesis that after controlling for gender and age, there would be significant positive correlations among maladaptive personality traits, dysfunctional attitudes, and psychological distress. A structural equation model with an excellent fit (CMIN/df = 2.23, p = .063, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.99, SRMR, = 0.01, and RMSEA = 0.04) provided partial support for the second hypothesis in that dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts mediated the relationship between maladaptive personality traits and psychological distress. Specifically, negative affectivity and detachment’s relationship with psychological distress were partially mediated via dysfunction attitudes and unhelpful thoughts, and dysfunctional attitudes respectively. These findings suggest that while dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thinking contribute to the relationship between personality traits and psychological distress, identification of other factors are required to improve theoretical understanding and subsequently psychological interventions.

Introduction

Psychological distress is transdiagnostic, in that it features in all psychiatric disorders, and is defined as a combination of stress, anxiety and depressive symptoms in response to daily or chronic stressors (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995; Barry et al., 2020). Gender and age represent the main biological predictors of psychological distress, with literature suggesting females experience significantly more psychological distress than males (Bracken & Reintjes, 2010; Mirowsky & Ross, 2017; Watkins & Johnson, 2018). Further, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW; 2018) found that – irrespective of gender – psychological distress increased throughout adulthood peaking at middle age (~ 50 years), before gradually decreasing. In addition to the biological contributors, two important psychological factors found to influence psychological distress are dysfunctional attitudes and personality (Buschmann et al., 2018; Jourdy & Petot, 2017).

Dysfunctional attitudes/beliefs reflect the attention, encoding, and interpreting of information in a negatively based format (Beck, 1976). Examples of these include rigid ‘must’ statements (e.g., “Everyone must love me’) and extreme “if-then” rules such as “If I do not pass this exam, then this confirms I am stupid”. A meta-analysis by Vîslă et al. (2016) found that across 83 primary studies including both clinical and community samples, dysfunctional attitudes predicted 20% of psychological distress variance independent of age, gender, income, educational, occupational, and marital status. Dysfunctional attitudes have also been identified to precede and perpetuate unhelpful thoughts (also known as thinking errors, negative automatic thoughts, or cognitive distortions) such as filtering, polarized thinking, overgeneralizing, and catastrophising (McKay et al., 2011). Understandably, like dysfunctional attitudes, unhelpful thoughts have been found to be related to, or associated with, changes in depression and anxiety (DeRubeis et al., 2008; Ross et al., 1986). Due to their significant role in underpinning and perpetuating psychological distress, dysfunctional attitudes and/or unhelpful thoughts are often primary targets for clinicians using psychological interventions such as cognitive behaviour therapy (Beck & Clark, 1997; Bowler et al., 2012; DeRubeis et al., 2008).

Along with dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thinking patterns, another primary contributor linked to psychological distress is personality traits (i.e., enduring patterns of perception, relation and thinking of the environment and oneself that are expressed in a wide variety of social and personal contexts; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Although the current approach for classifying personality disorders is based on the much-criticised categorial approach (e.g., Bach & Sellbom, 2016; Widiger & Gore, 2014), the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5; APA, 2013) took tentative steps to move towards a dimensional approach to personality-based psychopathology (referred to as the alternative model of personality disorders; AMPD). According to the AMPD, personality disorders are dichotomous, and thus evaluated by both the level of personality dysfunction, and the specific personality traits (i.e., negative affectivity, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism) which mirror the dysfunction. Recent literature supports the AMPD’s validity and usability across multiple mental health disorders including psychological distress (Chauhan et al., 2023; Clark & Watson, 2022; Nysaeter et al., 2023; Uliaszek et al., 2023; Vittengl et al., 2023).

Research to date provides evidence that personality traits, such as those based on the Big Five personality model (i.e., openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) account for approximately one third of variance in depression symptoms, with the trait neuroticism (the tendency to experience negative emotions) being the most frequent and strongest contributor (Strickhouser et al., 2017; Kotov et al., 2010). More broadly, neuroticism has been identified to both predict and perpetuate psychological distress (Pollak et al., 2020; Widiger & Oltmanns, 2017).

Given personality traits, unhelpful thoughts, and dysfunctional attitudes independently predict psychological distress, it may be unsurprising the three variables are strongly interrelated. Research indicates that neuroticism is particularly correlated with dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts (Blau et al., 2006; Hopwood et al., 2013; Samar et al., 2013). However, less is known about the role dysfunction attitudes and unhelpful thoughts play in the relationship between personality traits and psychological distress. Specifically, there is a lack of research examining whether dysfunctional attitudes and/or unhelpful thoughts mediate the relationship between personality traits and psychological distress.

Using a sample comprised of undergraduate psychology students, McDermut et al. (2019) found dysfunctional attitudes significantly and partially mediated the relationship between personality traits and psychological distress, and concluded that personality traits predicted psychological distress via the mechanism of dysfunctional attitudes. However, findings from McDermut et al. (2019) were limited by a relatively small sample size (n = 167), using just one personality trait (neuroticism) in the mediation model, and not investigating potential mediating role of unhelpful thoughts in personality-related psychological distress.

Given the limited research to date, this study aimed to examine the role of dysfunctional attitudes and/or unhelpful thoughts in personality traits and psychological distress. The study will also seek to address the limited research using Personality Inventory for DSM-5 brief form (PID-5-BF) which assesses the five personality traits (i.e., negative affectivity, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism) underpinning the AMPD. It was hypothesised that after controlling for gender and age, there would be significant positive correlations among personality traits, unhelpful thoughts, dysfunctional attitudes, and psychological distress. It was also hypothesised that dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts would mediate the relationship between personality traits and psychological distress.

Method

Participants and design

This study was based on an observational cross-design design using a convenience sampling method. Seven hundred and twenty-eight first year undergraduate psychology students enrolled at a medium-sized Australian university completed an online survey. The sample was predominantly female (76%), married/defacto (48.8%), and aged ranged between 18 and 74 years (M = 31.57, SD = 20.84).

Materials

Depression anxiety and stress scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995)

The DASS-21 is a 21-item self-report questionnaire which assesses psychological distress via three subscales each containing seven items: depression, anxiety, and stress. Participants were requested to report the degree to which each item (e.g., ‘I felt I had nothing to look forward to’) applied to them during the preceding week. Each item is measured on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (‘never’) to 3 (‘almost always’). As the DASS-21 is a short-form version of the original 42-item DASS, the final score was multiplied by two. Thus, total scores range from 0 to 126, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of psychological distress. The DASS-21 is reliable and valid amongst undergraduate student populations (Lemma et al., 2012; Osman et al., 2012), whilst demonstrating excellent internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.94).

Dysfunctional attitude scale-short-form 1 (DAS-SF1: Beevers et al., 2007)

The DAS-SF1 assesses dysfunctional attitudes across multiple domains including the need for approval from others (e.g., “My value as a person depends greatly on what others think of me”). Each item is scored on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (‘totally disagree’) to 4 (‘totally agree). Total scores range from 9–36 with higher scores indicating more severe dysfunctional attitudes. In this study, the short-form version of the DAS (i.e., DAS-SF1) was used to decrease participant burden. The DAS-SF1 has displayed sound psychometrics amongst undergraduate student populations (McDermut et al., 2019) and good internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.87).

The brief unhelpful thinking scale (BUTS; Knowles et al., 2017)

The BUTS is an 11-item questionnaire examines unhelpful thoughts across several domains such as polarised thinking (e.g., “Things are either black or white, good or bad”). Each item is scored on a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree). Total scores range from 0–55 with higher scores indicating greater tendency toward unhelpful thinking. The BUTS demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.82).

The PID-5 – Brief Form (PID-5-BF; Krueger et al., 2013)

The PID-5-BF comprises 25 items with five items for five personality traits: Negative affectivity, Detachment, Disinhibition, Antagonism, and Psychoticism. Each item asked respondents whether they felt a statement accurately described them (e.g., ‘I often have to deal with people who are less important than me’). Items were measured on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (‘Very False or Often False’) to 3 (‘Very True or Often True’). Each trait domain score ranged from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating greater personality trait dysfunction. The PID-5-BF is a reliable and valid instrument among university students which its brevity was designed to reduce participant burden (Anderson et al., 2018). The PID-5-BF demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this study (Cronbach’s α = 0.90).

Procedure

Participants were provided a link to the study via course research experience program. Prior to commencing, students were informed that their survey was intended for respondents aged 18 years old and above, their participation was voluntary, they had a right to withdraw any time without reasons, and their responses were anonymous. Agreeing to begin the survey implied informed consent. Following completion of the questionnaire, information was provided explaining the study’s purpose, and contact information for support was provided in the unlikely event that completing the survey caused psychological distress. Course credit was given in compensation for completing the study survey. Ethical approval for the study was obtained by the university human research ethics committee. Pre-testing of the online (Qualtrics) questionnaire was tested by the members of the research team. The questionnaire took approximately 30 min to complete with all questions requiring a response to minimise missing data.

Data analysis strategy

All analyses were performed with SPSS (version 27) and AMOS (version 27) Data were screened, and all assumptions were tested prior to analyses. Bivariate correlations and Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) were performed to examine the relationships of the demographic variables age and gender with study variables, evaluating the first hypothesis. The mediation model employing structural equation modeling was developed to evaluate the second hypothesis and the model fit being evaluated using the following criteria recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999): CMIN/Chi-square goodness of fit test [χ²] p > .05; Normed Chi-square [χ2/df] = 1–3, Tucker–Lewis index [TLI] > 0.95, Steiger-Lind Root Mean Square Error of Approximation [RMSEA] < 0.08, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual [SRMR] < 0.06. The final model was derived by a stepwise approach of adding or removing paths based on theoretical and AMOS reported modification indices.

Results

There were significant positive correlations among psychological distress, dysfunctional attitudes, unhelpful thoughts, and all five PID-5 personality traits (See Table 1). Psychological distress, dysfunctional attitudes, and the PID-5 personality traits were negatively correlated with unhelpful thinking. Negative affectivity produced the strongest correlations with psychological distress (r = .59), unhelpful thinking (r = .59), and dysfunctional attitudes (r = .54). Detachment produced moderate correlations with psychological distress (r = .45), unhelpful thinking (r = .42), and dysfunctional attitudes (r = .43). Unhelpful thoughts were also strongly correlated with dysfunctional attitudes (r = .59) and psychological distress (r = .52). Age was found to be a significantly related to negative affectivity (r = −.29, p < .001), detachment (r = − .10, p = .01), disinhibition (r = − .22, p < .001), psychoticism (r = − .26, p < .001), antagonism (r = − .27, p < .001), Unhelpful thinking (r = .27, p < .001), Dysfunctional attitudes (r = - .21, p < .001), and psychological distress (r = − .21, p < .001), and therefore age was controlled for in the subsequent analysis. A MANOVA (IV: gender; DVs: study variables) identified result was significant for gender, Pillai’s Trace = 0.01, F(14,1428) = 5.42, p < .001. A subsequent, univariate F test indicated that females had a significantly higher mean psychoticism compared to males (F (2,719) = 3.35, p = .036). No other gender-based difference across the study variables was found.

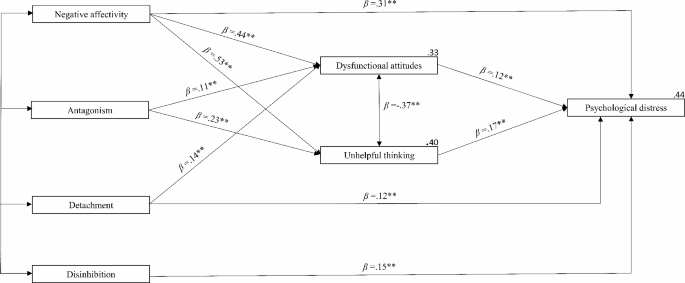

In relation to the second hypothesis, a final model was developed based on an iterative approach where nonsignificant paths were removed from a saturated mediation model. Initially the model controlled for age and gender, however its inclusion produced a poorer fit and was therefore removed from the model. Similarly, psychoticism found to be a poor predictor and was also removed from the model. Overall, the final model (see Fig. 1) had an excellent fit (CMIN/df = 2.23, p = .063, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.99, SRMR, = 0.01, and RMSEA = 0.04). The total amount of variance accounted for in each of the variables was 33% of dysfunctional attitudes, 40% of unhelpful thinking, and 44% of psychological distress. As shown in Fig. 1, Disinhibition had a significant direct influence on psychological distress and the relationship between Antagonism and psychological distress is fully mediated via BUTS and DAS-SF. The relationship between Negative affectivity and psychological distress is partially mediated via BUTS and DAS-SF while the relationship between Detachment and psychological distress is partially mediated via DAS-SF. The configural model fit indices indicated an adequate fit (χ2(36) = 1.65, p = .009, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.02, Akaike information criterion (AIC) = 155.28), and the measurement weights model, with equal factor loadings on males and female groups, fit indices were also acceptable (χ2(46) = 1.42, p = .031, TLI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.02, AIC = 144.47). Comparisons across models showed that the increase in chi-squared values (Δχ2(10) = 6.19, p = .799) was not statistically significant and changes in other model fit indices were small, indicating robust measurement consistency across gender.

Discussion

The results supported the first hypothesis in that after controlling for gender and age, there would be significant positive correlations among PID-5 personality traits, dysfunctional attitudes, and psychological distress. These findings were consistent with the cognitive theory model linking these variables (Góngora & Castro Solano, 2017; Hopwood et al., 2013; Kotov et al., 2010; Pretzer & Beck, 2005). Also consistent with past research were the findings that Negative affectivity and Detachment produced the strongest correlations with psychological distress, dysfunctional attitudes, and the significant positive correlations between all five PID-5 personality traits and dysfunctional attitudes (Hakulinen et al., 2015; Hopwood et al., 2013; McDermut et al., 2019; Thimm et al., 2016). Additionally, there were no significant differences between male and female for individuals concerning dysfunctional attitudes, unhelpful thoughts, psychological distress, and personality traits, except for psychoticism.

The results also partially supported the second hypothesis in that dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts would mediate the relationship between PID-5 personality traits and psychological distress. Specifically, Negative affectivity and Detachment’s relationship with psychological distress were partially mediated via dysfunction attitudes and unhelpful thoughts, and dysfunctional attitudes respectively. Further, supporting the second hypothesis was the finding that Antagonism’s effect on psychological distress was fully mediated by both dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts. Not supporting the second hypothesis were the findings that neither dysfunctional attitudes nor unhelpful thoughts had any impact on Disinhibition’s effect on psychological distress.

The partial mediation of dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts upon Negative affectivity’s relationship with psychological distress was consistent with McDermut and colleagues’ (2019) findings, and subsequently indicates that Negative affectivity predicts psychological distress, at least partially, by operating through these two cognitive mediators. Moreover, the novel findings that dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts fully explained the relationship between Antagonism and psychological distress suggests they are the primary cognitive processes inherent within this relationship. Conversely, neither dysfunctional attitudes nor unhelpful thoughts had any impact upon Disinhibition’s relationship with psychological distress which indicates that this relationship exists outside of these cognitive models linking personality and psychological distress (Beck et al., 2015).

Clinical implications

The findings suggest that dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts play a role in explaining the relationship between psychological distress and the AMPD PID-5 personality traits Negative affectivity, Detachment, and Antagonism. Subsequently, clients who present with psychological distress and score highly on these three scales may benefit from therapeutic interventions which focus on clients’ attitudes and unhelpful thinking patterns via well-established approaches such as cognitive behavioural therapy. Antagonism specifically, may be efficaciously treated by interpersonal therapy (IPT) given that it’s key feature interpersonal problems (Vize et al., 2022; Wright, 2019). Conversely, this approach may not be as efficacious for clients scoring high on Disinhibition, as this trait’s characteristics include irresponsibility, impulsivity, and risk taking; all of which infer potential treatment-interfering behaviours including missed appointments, difficulty focusing in-session, and nonadherence to homework tasks (APA, 2013). The utilisation of an intervention to such specific personality traits may be more efficacious, rather than focusing on attitudes and thoughts which may be symptoms of the trait. For instance, Conrod et al. (2013) created personality-specific interventions which included psychoeducation of personality traits and goalsetting to enhance motivation to change. The authors found that the intervention significantly reduce disinhibition-related behaviours (i.e., substance use) among adolescents. However, more research is required to determine the efficacy of this approach across wider community and clinical populations.

Limitations and future studies

This study has several limitations. The cross-section design lacks the robustness of a longitudinal approach from which casual inferences (true mediation) could be attained. The study also utilised a largely homogeneous non-clinical convenience sample of university students thus limiting the generalisability of findings, including age, cultural, socioeconomic, and educational diversity. It is also important to recognise the potential impact and limitations associated with social desirability and selection and response bias given the student-based convenience sample. Future research should investigate if these results can be replicated using community and clinical populations. Additionally, this paper utilised dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts broadly. A more judicious approach might be to explore which specific dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts are associated with specific personality traits. This could improve theory and potentially offer a more targeted approach to treating personality-related psychological distress.

In addition to addressing the above limitations, future studies should also look to explore and address other potential processes or confounders which may influence the identified relationships. These include coping strategies, comorbid psychological and/or physical conditions, and psychosocial stressors (e.g., relationship, employment, educational, financial). For instance, Huang et al. (2021) found that other psychological processes such as self-efficacy, coping styles, and psychological resilience mediated this relationship between personality traits and psychological distress among Chinese nurses. Similarly, a recent paper by Kestler-Peleg and colleagues (2023) found intolerance to uncertainty mediated the relationship between personality traits and a form on adjustment disorder-associated psychological distress.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study’s findings indicate that three AMPD PID-5 personality traits (i.e., Negative affectivity, Detachment, and Antagonism) predicted psychological distress via the dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts. This study is the first to extend the limited research to date by exploring the potential mediating role of dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts on the relationship between personality and psychological distress. The findings provide evidence for the mediating role of dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts. While limited by the cross-sectional design and evidence for true causal mediation, the findings highlight the relevance and importance of targeting dysfunctional attitudes and unhelpful thoughts in therapy.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and after relevant ethical approval.

References

-

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

-

Anderson, J. L., Sellbom, M., & Salekin, R. T. (2018). Utility of the personality inventory for DSM-5-Brief form (PID-5-BF) in the measurement of maladaptive personality and psychopathology. Assessment, 25(5), 596–607. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116676889

-

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2018). Australia’s Health 2018. (Cat. No. AUS 221; Australia’s Health Series No. 16), 570. https://doi.org/10.25816/5ec1e56f25480

-

Bach, B., & Sellbom, M. (2016). Continuity between DSM-5 categorical criteria and traits criteria for borderline personality disorder. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(8), 489–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743716640756

-

Barry, V., Stout, M. E., Lynch, M. E., Mattis, S., Tran, D. Q., Antun, A., Ribeiro, M. J., Stein, S. F., & Kempton, C. L. (2020). The effect of psychological distress on health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(2), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105319842931

-

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders New York, New American Library.

-

Beck, A. T., & Clark, D. A. (1997). An information processing model of anxiety: Automatic and strategic processes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(96)00069-1

-

Beck, A. T., Freeman, A., & Davis, D. D. (2015). Cognitive therapy of personality disorders 3rd edition / New York, The Guilford Press.

-

Beevers, C. G., Strong, D. R., Meyer, B., Pilkonis, P. A., & Miller, I. R. (2007). Efficiently assessing negative cognition in depression: An item response theory analysis of the dysfunctional attitude scale. Psychological Assessment, 19(2), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.199

-

Blau, S., Fuller, J. R., & Vaccaro, T. P. (2006). Rational-emotive disputing and the five-factor model: Personality dimensions of the Ellis emotional efficiency inventory. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 24(2), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-005-0020-z

-

Bowler, J. O., Mackintosh, B., Dunn, B. D., Mathews, A., Dalgleish, T., & Hoppitt, L. (2012). A comparison of cognitive bias modification for interpretation and computerized cognitive behavior therapy: Effects on anxiety, depression, attentional control, and interpretive bias. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(6), 1021–1033. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029932

-

Bracken, B. A., & Reintjes, C. (2010). Age, race, and gender differences in depressive symptoms: A lifespan developmental investigation. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 28(1), 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282909336081

-

Buschmann, T., Horn, R. A., Blankenship, V. R., Garcia, Y. E., & Bohan, K. B. (2018). The relationship between automatic thoughts and irrational beliefs predicting anxiety and depression. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 36(2), 137–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-017-0278-y

-

Chauhan, K., Donahue, J., & Thompson, R. (2023). The predictive validity of the DSM-5 alternative model for borderline personality disorder: Associations with coping strategies, general distress, rumination, and suicidal ideation across one year. Personality and Mental Health, 17(3), 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.1580

-

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (2022). The trait model of the DSM-5 alternative model of personality disorder (AMPD): A structural review. Personality Disorders, 13(4), 328–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000568

-

Conrod, P. J., O’Leary-Barrett, M., Newton, N., Topper, L., Castellanos-Ryan, N., Mackie, C., et al. (2013). Effectiveness of a selective, personality-targeted prevention program for adolescent alcohol use and misuse: A cluster randomized controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(3), 334–342. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.651

-

DeRubeis, R. J., Siegle, G. J., & Hollon, S. D. (2008). Cognitive therapy versus medication for depression: Treatment outcomes and neural mechanisms. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(10), 788–796. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2345

-

Góngora, V. C., & Castro Solano, A. (2017). Pathological personality traits (DSM-5), risk factors, and Mental Health. SAGE Open, 7(3), 2158244017725129. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017725129

-

Hakulinen, C., Elovainio, M., Pulkki-Råback, L., Virtanen, M., Kivimäki, M., & Jokela, M. (2015). Depression and Anxiety, 32(7), 461–470. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22376

-

Hopwood, C. J., Schade, N., Krueger, R. F., Wright, A. G., & Markon, K. E. (2013). Connecting DSM-5personality traits and pathological beliefs: Toward a unifying model. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 35(2), 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-012-9332-3

-

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

-

Huang, W., Cai, S., Zhou, Y., Huang, J., Sun, X., Su, Y., Dai, M., & Lan, Y. (2021). Personality profiles and personal factors Associated with psychological distress in Chinese nurses. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 14, 1567–1579. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S329036

-

Jourdy, R., & Petot, J. M. (2017). Relationships between personality traits and depression in the light of the big five and their different facets. L’Évolution Psychiatrique, 82(4), e27–e37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evopsy.2017.08.002

-

Kestler-Peleg, M., Mahat-Shamir, M., Pitcho-Prelorentzos, S., & Kagan, M. (2023). Intolerance to uncertainty and self-efficacy as mediators between personality traits and adjustment disorder in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychology (New Brunswick N J), 42(10), 8504–8514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04465-9

-

Knowles, S. R., Apputhurai, P., & Bates, G. (2017). Development and validation of the brief unhelpful thoughts scale (BUTs). Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy, 4, 61–70. https://savvysciencepublisher.com/index.php/jppr

-

Kotov, R., Gamez, W., Schmidt, F., & Watson, D. (2010). Linking big personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(5), 768–821. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020327

-

Krueger, R., Derringer, J., Markon, K., Watson, D., & Skodol, A. (2013). The personality inventory for DSM-5—brief form (PID-5-BF)—adult. American Psychiatric Association.

-

Lemma, S., Gelaye, B., Berhane, Y., Worku, A., & Williams, M. A. (2012). Sleep quality and its psychological correlates among university students in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Bmc Psychiatry, 12(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-237

-

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u

-

McDermut, W., Pantoja, G., & Amrami, Y. (2019). Dysfunctional beliefs and personality traits. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 37(4), 338–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-019-00315-5

-

McKay, M., Davis, M., & Fanning, P. (2011). Thoughts and feelings: Taking control of your moods and your life. New Harbinger.

-

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (2017). Social causes of psychological distress (2nd ed.). Routledge.

-

Nysaeter, T. E., Hummelen, B., Christensen, T. B., Eikenaes, I. U., Selvik, S. G., Pedersen, G., Bender, D. S., Skodol, A. E., & Paap, M. C. S. (2023). The Incremental Utility of Criteria A and B of the DSM-5 Alternative Model for Personality disorders for Predicting DSM-IV/DSM-5 section II personality disorders. Journal of Personality Assessment, 105(1), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2022.2039166

-

Osman, A., Wong, J. L., Bagge, C. L., Freedenthal, S., Gutierrez, P. M., & Lozano, G. (2012). The Depression anxiety stress Scales-21 (DASS-21): Further examination of dimensions, scale reliability, and correlates. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(12), 1322–1338. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21908

-

Pollak, A. J., Dobrowolska, M., Timofiejczuk, A., & Paliga, M. M. (2020). The Effects of the Big Five Personality Traits on Stress among Robot Programming Students. Sustainability, 12, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125196

-

Pretzer, J. L., & Beck, A. T. (2005). A cognitive theory of personality disorders. In M. F. Lenzen- weger & J. F. Clarkin (Eds.), Major Theories of Personality Disorder (2nd ed., pp. 43–113). New York, The Guilford Press.

-

Ross, S. M., Gottfredson, D. K., Christensen, P., & Weaver, R. (1986). Cognitive self-statements in depression: Findings across clinical populations. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 10(2), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01173722

-

Samar, S. M., Walton, K. E., & McDermut, W. (2013). Personality traits predict irrational beliefs. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 31(4), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-013-0172-1

-

Strickhouser, J. E., Zell, E., & Krizan, Z. (2017). Does personality predict health and well-being? A metasynthesis. Health Psychology, 36(8), 797–810. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000475

-

Thimm, J. C., Jordan, S., & Bach, B. (2016). The personality inventory for DSM-5 short form (PID-5-SF): Psychometric properties and association with big five traits and pathological beliefs in a Norwegian population. BMC Psychol, 4(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0169-5

-

Uliaszek, A. A., Amestoy, M. E., Fournier, M. A., & Al-Dajani, N. (2023). Criterion a of the alternative model of personality disorders: Structure and validity in a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 35(5), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001225

-

Vittengl, J. R., Jarrett, R. B., Ro, E., & Clark, L. A. (2023). How can the DSM-5 alternative model of personality disorders advance understanding of depression?. Journal of Affective Disorders, 320, 254–262.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.09.146

-

Vîslă, A., Flückiger, C., Holtforth, G., M., & David, D. (2016). Irrational beliefs and psychological distress: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 85(1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1159/000441231

-

Vize, C. E., Ringwald, W. R., Edershile, E. A., & Wright, A. G. C. (2022). Antagonism in Daily Life: An exploratory ecological momentary Assessment Study. Clinical Psychological Science, 10(1), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026211013507

-

Watkins, D. C., & Johnson, N. C. (2018). Age and gender differences in psychological distress among African americans and whites: Findings from the 2016 National Health interview survey. Healthcare (Basel Switzerland), 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6010006

-

Widiger, T. A., & Gore, W. L. (2014). Dimensional versus categorical models of psychopathology. The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp108

-

Widiger, T. A., & Oltmanns, J. R. (2017). Neuroticism is a fundamental domain of personality with enormous public health implications. World Psychiatry, 16(2), 144–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20411

-

Wright, A. G. C. (2019). Antagonism from the perspective of interpersonal theory. In J. D. Miller, & D. R. Lynam (Eds.), The handbook of antagonism: Conceptualizations, assessment, consequences, and treatment of the low end of agreeableness (pp. 155–170). Elsevier Academic. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814627-9.00011-6

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the individuals who participated in this research.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

-

Department of Psychological Sciences, Swinburne University of Technology, John St, Hawthorn, Melbourne, VIC, 3122, Australia

Ronan J. Galloghly & Simon R. Knowles

-

Department of Health Science and Biostatistics, School of Health Sciences, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, Australia

Pragalathan Apputhurai

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Simon R. Knowles.

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

Informed consent to publish the study findings was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interests in relation to this study.

Get Support

Please make an enquiry if you would like to book an appointment for one of our services. Alternatively, you can live chat with us during business hours.